Gods, Kings and other Idiots

“Gods, Kings, and Other Idiots”: In this sarcastic glimpse into ancient Martian life, a frustrated bureaucrat recounts the chaotic launch of Earth’s “Valhalla project.” With meddling elites posing as gods and genetic experiments gone awry, humanity’s origin story turns into a cosmic joke.

Produced by J.August Jackson sith support from ChatGPT, MidJourney, and ElevenLabs. A podcast version is available on Spotify.

Let me begin by saying that none of this was at all my fault.

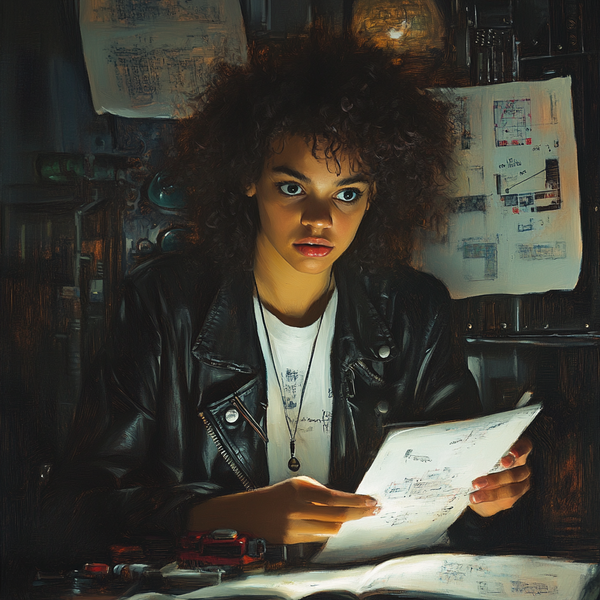

Sure, I had technically approved the first batch of humans. But the genetics department was breathing down my neck to meet appalling deadlines, the planetary stability board was slashing my budget quarterly, and the High Council of Eternal Something-or-Other, had been tirelessly shifting the project scope. What else could anyone have done under the circumstances?

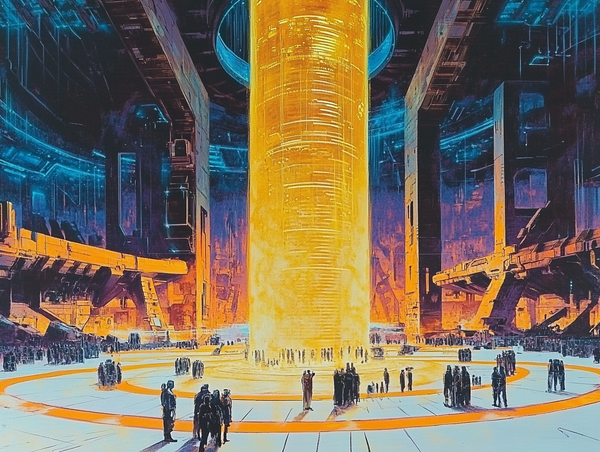

You see, the real problem wasn’t the humans. In fact, the humans were actually one of the better ideas we'd come up with—adaptable, curious, not too bright... An unquestionably perfect species for a long-term experiment. The issue was the target planet. Earth, as we commonly refer to it now, or, as the idiots in charge at the time, liked to call it back then: Valhalla.

Right from the start, the whole thing was a logistical nightmare. Earth wasn’t supposed to be a thriving civilization—just a hobby planet, a little side project for the elites. Somewhere they could get away from the politics and overcrowding back home. The plan was simple: seed the planet with some flora and fauna, run a few experiments, and in a few thousand years, we’d have ourselves a nice vacation spot.

But as a matter of course, in those times, the Council inserted itself, and as one would expect, the Council began suggesting fabulous ideas, and everything went straight to hell.

Councilor Ishti had said, “We need mythological constructs,” waving his hand like mythology was something you could download from a shared library. “Gods, kings, rituals—it’s all part of the aesthetic. Humans love that sort of thing.”

I'd pointed out that the humans we’d designed so far didn’t love anything, since they were still wandering around in animal skins, hiding from enormous beasts, and otherwise arguing with large rocks.

"Details," Ishti had said, with his smug little smile that only someone with no idea what they're talking about can get away with professionally. "We'll give them gods! Entire Pantheons! It'll give them a sense of purpose."

This was exactly what we needed at the time. We'd spent decades perfecting the food chain, balancing predator-prey ratios, and establishing elegant and diverse, even edible mycelia garbage collection, and now, this! I knew that I was about to be compelled, with little to no support from my colleagues, to spend my foreseeable evenings and weekends with inventing and balancing several various systems of religion.

I'd asked if we could at least agree on one pantheon—something simple. Maybe we could use the same template of the same four or five gods per region, each in charge of a major concept: sun, rain, love, and so on.

Naturally, the Council overruled me. They decided that every region on Earth should get its own unique gods. “Variety,” they said. “Humans thrive on cultural diversity.”

What they meant, of course, was: “We want to outdo each other’s gods, and we want to see who can cause the most chaos doing it.”

I've lost track of how many gods we'd ended up with. At one point, I think the count was somewhere north of six hundred, but by then the project had taken on a life of its own.

One Councilor had created a god who demanded human sacrifices. Another countered with a goddess of fertility who made it rain frogs twice a year. Somewhere in the middle of all this, the geneticists accidentally created, what humans now call the Neanderthals, which—let me tell you—was an awkward memo to draft for the Council to say the very least.

“Shall I simply shut them down then?” I'd asked at a rather lengthy strategy meeting, thinking they’d jump at the chance to cull some of the chaos.

Instead, they just shrugged.

“They’re interesting,” said Councilor Arel. “Let’s see what happens.”

Let’s see what happens. That should be the official Martian motto.

The real mess started when the elite class began making unauthorized trips to Valhalla. They were supposed to stay on Mars and oversee things remotely, but no, they couldn’t resist showing off their divine personas to the locals. You give a bored aristocrat access to a primitive planet, and suddenly half the Council is running around pretending to be sun gods and sea spirits on holiday.

One self-righteous party goer—Canthos—not to be out done, actually convinced an entire civilization that he was the one and only god of war, just so they’d build statues of him, never mind that they laid waste to dozens of neighboring peoples in his name. It was ridiculous. The humans worshipped him, threw festivals in his honor, the whole nine yards. Meanwhile, back on Mars, Canthos couldn’t even parallel park without assistance.

And don’t even get me started on the genetic experiments. Half of the so-called “mythical creatures” humans still tell stories about—centaurs, mermaids, whatever—they weren’t divine gifts. They were screw-ups.

Do you think anyone would intentionally cross-breed a horse with a man? Of course not. Some idiot in genetics had simply forgotten to lock the hybrid tanks, and now we have the legend of Hercules riding around on his centaur friend.

By the time anyone had realized things were spiraling out of control on Valhalla, it had become far too late to do much about it. Mars had its own problems—resource shortages, political unrest, inevitable collapse of recycling infrastructure, and the complete democratization of global news channels, fracturing the global narrative into hundreds of perspectives of unsubstantiated opinion. Basic global upheaval stuff.

The Council quietly shifted their focus back to Mars, leaving Valhalla—sorry, Earth—to sort itself out. “The humans will be fine,” they said. “We’ve given them gods.”

Of course, the humans weren’t fine. They immediately started fighting over whose god was better, and the whole thing devolved into millennia of bloodshed. But hey, at least the statues were nice.

And now here we are. Mars is a wasteland, Earth is an overcrowded mess, and I’m stuck in a tiny office trying to clean up the aftermath of a planetary experiment gone horribly wrong.

Sometimes I wonder what would’ve happened if we’d just given the humans Netflix instead of mythology. But no, the Council wanted gods. They wanted chaos. They wanted statues of themselves in bronze and marble, scattered across the surface of a planet they don’t even visit anymore.

Well, they got it.

Gods, kings, and other idiots. That’s what this whole thing boils down to.