Saknarth

Set on Mars, this story revolves around Saknarth, a Master Astrologer at the Imperial Observatory. Despite skepticism towards astrology, Saknarth discovers lights on the dark side of Earth, challenging his and his society's beliefs.

Written by: Donald A. Wollheim

Provided by: Project Gutenberg

"The lights upon the Morning Star." How well he remembered that phrase. Twenty years it must have been since Kwarit had whispered it to him, at the great trial where they had accused Kwarit of heeding the signals of the Evil One.

As he had been led away, he had managed to whisper to young Saknarth, then a mere neophyte, the strange phrase that had lingered, echoing and reechoing through the young student's mind all these years. From neophyte to the Master Astrologer of the Imperial Observatory. It would be more than forty years by the third planet's hurried pace. Did the lights still glow upon the Morning Star?

Saknarth glanced over at the chronometer. It would be a half hour before the Morning Star rose. There was work to be done; he must prepare the day's horoscope. He laughed to himself. What fools priests and rulers must be to believe that the stars foretold the future. What an upset if they learned how it all originated in the minds of astrologers—no more the guesswork based upon a knowledge of the past. Well, so far, thought Saknarth, my forecasts have been more or less true.

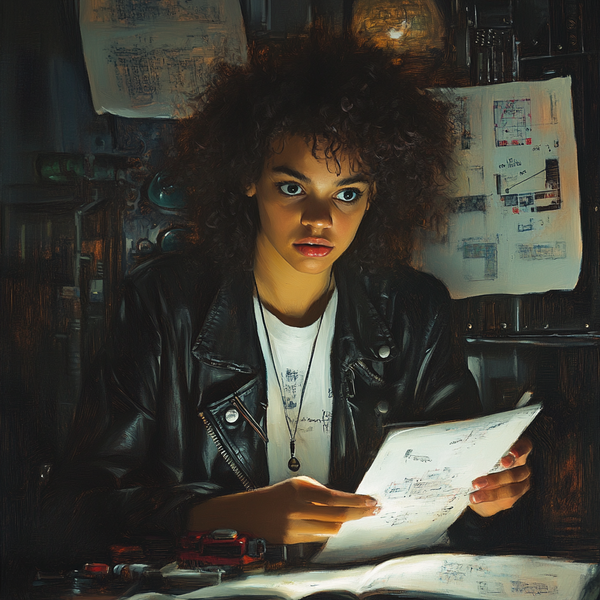

Seating himself at a little desk in the shaded glow of an oil lamp, he proceeded to write his prophecies, taking care to befog them with astrological formulae and mystic bosh.

A half hour passed. Already a dim light glowed deep in the eastern horizon. Now from low in the sky a blue star gleamed, a steady glowing mote of light heralding the dawn. The Morning Star.

Saknarth pushed back his stool from the desk and stood up. He glanced through the open panel at the planet. Then over to the largest telescope in the observatory, a twenty inch reflector. He applied his single round eye to the eyepiece and gazed at great Kurnal, largest of the inner planets.

A crescent of brilliant light, the major part of it dark. It was nearing its closest, Saknarth thought. The sun was behind it and the night side was presented to Mars. The thin crescent glowed brightly. He could see dimly dark shading of landmasses in that area, but the rest was dark, unlit.

Saknarth reflected. Here it was that Kwarit had seen his lights, in the dark of the Earth. But then he was using a bigger instrument; he was using the great fifty inch reflector, largest ever made. That had been removed. The priests had said that it was accursed of the Devil and they had taken it and placed it in the Hall of Evil Things. None were permitted to look through it. Saknarth swore softly to himself. Oh for a glimpse through it, for a single glance—

The day was nearly over. Saknarth had delivered his horoscope to the Emperor and had served his moments at the court; now he was wending his way homeward through the narrow streets of Lucas Phoenicus. He saw before him a great building, the Imperial Museum. Suddenly a thought struck him; he would like to see Kwarit's telescope.

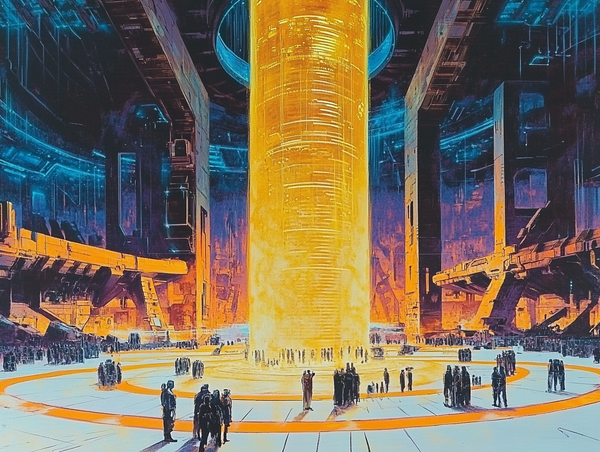

Accordingly he entered the vast institute. Through the long passages he went, past the exhibits of stuffed beasts and catalogued plants, and the many rooms of ancient empires and lost peoples. Through all these he went into the wing where lay the Hall of Evil Things. This was well guarded he thought. Two helmeted and cuirassed soldiers stood before the entrance. Their single eyes gleamed suspiciously at all passers by, their stumpy horns capped by dangerous looking steel spikes, their hands resting upon huge maces at their sides. They halted Saknarth as he sought to enter, but he showed them his credentials as a member of the Imperial Court and was permitted to pass. Down the hall he strode, past cases of forbidden books, evil robes, devil haunted, and mummeries of all kinds to the very end where, behind an iron railing, stood the telescope.

The Master Astrologer leaned on the railing and stared at it. The huge mirror, kept in condition by the attendants, gleamed brilliantly. The great instrument at the end of the hall near the window, the Eastern sky visible. The sun rose in sight of that window, and the Morning Star. From where the telescope stood, it should be possible to train it on the planet.

The Master Astrologer became excited; he glanced around hurriedly for fear someone might have witnessed. Then carefully he took in all details of the lay of the room, turned and walked out.

It was dark. A chill wind from the deserts swept through the deserted streets of the Martian capital. A period of deepest silence when even the eternal thumping of the canal pumps died down to a dull distant hum. In the dim stretches of the hour before dawn the city was at its quietest. On the street corners a few sleepy guards leaned against walls and closed their single great eyes in rest for a moment.

Down a side street in the darkest shadows slipped a figure. Dark cloaked, treading upon cushioned toes, it crept from building to building, keeping as much as possible in the recesses of arches of the little carved balconies Martian buildings are wont to have. Finally the figure came to a halt in a doorway. It stood for a moment looking around to make sure of the place and then producing a long thin instrument, picked the lock and rolled aside the door.

Saknarth stepped softly inside the dark hallway, rolled the door shut. He listened a moment, then assured by silence tip-toed forward up the incline that he knew lay to one side of the hall. Up he climbed. Reaching a floor, he turned quickly and groped for the next incline, reached it and ascended again. Soon he came to where there were no more floors, and pushing aside a trap door, stepped out on the roof.

It was not so dark up here. The dim lights of the two tiny moons added to the lights of the myriad stars to cast a misty white glow upon objects.

The astrologer tip-toed silently across the roof onto an adjoining one. On he progressed to come finally to the great wall of a building looming up above. Set in this wall was a large window about fifteen feet above his head.

Saknarth groped under his cloak, drew out a long thin rope. To the end of this he fastened a small, strong double hook making an effective grappling iron.

He stepped back, whirled it around his head and tossed it upwards. It struck the wall just below the sill, bounded back. He waited and listened; no one had heard. Again he tossed the rope; and this time the hook caught in the carved decorations of the window sill.

Saknarth pulled; the rope held. He whispered a short prayer and grasping high on the rope raised his feet off the ground. Immediately he swung inward to touch the wall with his feet. Then, slowly and laboriously, climbed up the rope.

Reaching the sill, Saknarth threw a leg over and lay quiet for a moment. Still safe. He drew out his lock-picking instrument and easily opened the window enough to permit him to creep through and drop silently on the other side.

The long hall was dark and quiet. No one had heard him. He looked up. There next to him loomed the great telescope.

Saknarth stepped over the railing and perched himself on the observer's seat. He polished the eyepiece fondly, grasped the hand wheels. Turning these, he swung the heavy instrument downwards, down till it faced the open window and the coming dawn.

There, low in the heavens hung the Morning Star. It glowed brightly and seemed to beckon and encourage him on. He set the readings on the clockwork adjustment, applied his eye to the lens.

A brilliant crescent shining with the blue green radiance of the third planet. Much larger than ever the Master Astrologer had seen it. He stared eagerly at the now sharply outlined land masses visible, noting the green color of some and wondering if it could be the green of vegetation.

He drew his gaze from the bright crescent to stare at the dark portion. It was not truly dark. A dim grey light seemed to show up vague suggestions of continents and seas, the reflected light of Kurnal's huge moon, he thought. But the lights: he must look for the lights.

Long he stared and suddenly he saw them. A tiny dot of white light glowing in the center of the dark disc. Now several others caught his view; his heart thumped wildly. The lights were there; Kwarit had spoken truthfully. He stared avidly at them. Cities, he thought: could they be cities? He dismissed the thought as soon as it had come as being foolish. There were many. He tried to count them. Most were in the Northern half, yet there were one or two in the southern zone, too. Many on top and a few below. A strange sense of having seen that design before entered his mind. The arrangement was peculiar; he studied it closely.

The Sign of Dallon! He recognized it. The ideograph of Dallon the prophet was exactly like that. The Sign of Dallon on the face of Kurnal. The prophecy. He remembered it from his student days.

Dallon, one of the ancient founders of the priesthood, had declared; "Man shall be humble and bow down to the gods; he shall revere those who are their priests and prophets; he shall not deem to impose upon their domains and shall support and obey them. This shall be until the Sign of Dallon shall appear on the face of the Morning Star. Then will Man rise above the gods. And that time is Never."

The time had come; the priesthood should no longer enslave mankind. Now was learning and enlightenment to come to the people to give them conquest over fear and misery. And he, Saknarth, must tell the multitudes.

He continued thus, in his reveries, his lone eye glued to the great instrument, his mind seething with a multitude of thoughts.

A step sounded in the darkness. A hand was laid roughly upon his shoulder. He was jerked away from the eyepiece to face the two guards that had been patrolling the halls of the Museum. Saknarth opened his mouth. "I have seen on Kurnal—" he began, but a soldier clapped his hand over the astrologer's mouth and said gruffly, "Silence. Let not your mouth tell of the blasphemies seen through this instrument of the Devil." They gagged Saknarth and bound his hands and led him out of the hall, turned him over to imprisonment.

His trial was short and speedy. During the entire proceedings he remained gagged and bound so as to be unable to utter the blasphemies he might have seen. The priests passed quick judgment upon him for had he not been caught peering through the accursed instrument? There was naught for such but execution.

The guards led him out of the courtroom that morning and took him to a cell overlooking the place of execution. Here for the first time he was ungagged and unbound. The door rolled shut upon him and the locks clicked.

Saknarth gazed out of the barred window. The street was many feet below. He could not possibly shout down to the passers-by what he had learned. He looked wildly around him.

On a little table was parchment and crayon. He grasped these and quickly drew a series of ideographs. He wrote furiously for he had not much time.

He wrote about the lights and the Sign. He exhorted the reader to carry it to the astrologers and the men of learning. He declared the time had come to rise and strike for freedom.

Rising, Saknarth went over to the window, waiting. There were many going through the street below, but he waited for the best. There! A young man passing now. Upon his arm was the circle insignia of the Society of the One God. An intelligent look was in his eye.

Saknarth grasped the rolled manuscript and hurled it. Straight before the youth it fell. The young man picked it up, drew aside into a doorway opposite to read it. Hopefully the prisoner watched the expression on the youth's face, saw light spring into his eyes, saw a smile and a determined line spread over his face.

The reader looked up. Straight into Saknarth's eyes he gazed, then raised his hand in salute and hurried off down the street.

The Master Astrologer sat down upon his stool, waiting for the executioners. He was ready to die now; he had done his work.