Strangers To Straba

A gripping tale where a ship develops a sinister life of its own, leading to unforeseen and eerie consequences. The story masterfully combines elements of suspense and science fiction, exploring the dark intersections between technology and the unknown.

Written by: Carl Jacobi

Provided by: Project Gutenberg

Like Robert Bloch, Margaret St. Clair, Frank Belknap Long and the late great Howard P. Lovecraft, Carl Jacobi won his first bright laurels as a story teller in the "ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir." He was one of that early group of supernatural horror story writers who have since turned to science fiction, and achieved in the newer medium a fame quite as illustrious and quite as enduring. We know you'll like this somberly exciting yarn.

They sat in Cap Barlow's house on the lonely planet, Straba. It was early evening and Straba's twin moons were slowly rising from behind the magenta hills. Outside the window lay Cap's golf course, a study in toadstool cubism, while opposite the flag of the eighteenth hole squatted the kid's ship.

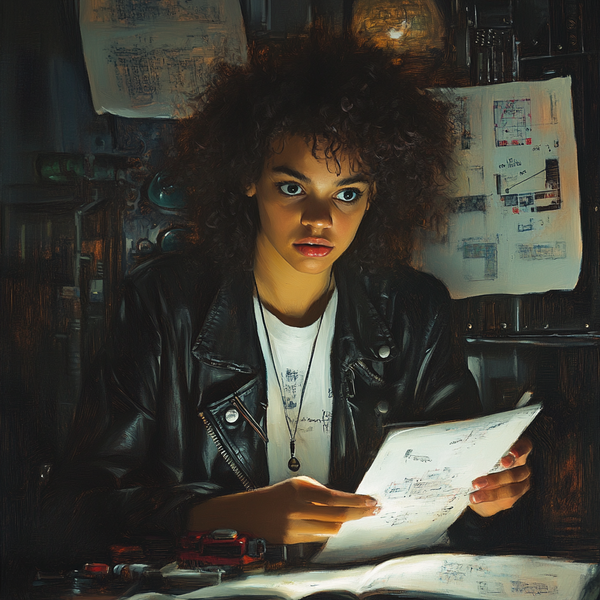

The kid had landed there an hour ago. He had introduced himself as Clarence Raine, field man for Tri-Planet Pharmaceutical, and had announced urbanely he had come to make a botanical survey. All of which mildly amused Cap Barlow.

The kid was amused too. From the Pilot Book he had learned that Cap was the sole inhabitant of Straba, and he regarded him—and rightly so—as just another hermit nut who preferred the spacial frontiers to the regular walks of civilization.

The old man packed and lit a meerschaum pipe.

"Yes sir," he said, "efficiency ... regulation ... order ... that's what's spoiling all life these days. Those addle-headed scientists aren't satisfied unless they can dovetail everything."

Raine smiled and in the pause that followed cast his eyes about the room. It was circular and no attempt had been made to conceal its origin: the bridge-house of some discarded space-going tug. Along the continuous wall ran a triple tier of bookshelves, but it seemed that most of the books lay scattered on the table, chairs, and floor.

Above the shelves the wall was decorated with several three-dimensional water colors, pin-up girls in various stages of undress and mounted trophies of the rather hideous game Straba provided.

"About this survey," the kid began.

"Only last month," Cap Barlow continued, unmindful of the interruption, "a salesman stopped off here and wanted to sell me a gadget for my golf course. Said it would increase the gravitation over the fairways and prevent the ball from traveling any farther than it does on Earth."

He spat disgustedly. "You'd think any fool would realize it's an ideal course that can offer a Par three on a thousand yard hole."

But Raine hadn't come this far to listen to the dissertations of an old man. He was tired from long hours of sitting at the console of his ship. He stood up wearily.

"If you'll show me where I can stow my gear," he said, "I think I'll turn in and get some sleep. I've got a lot to do tomorrow."

For a week the kid didn't bother Cap at all. Each morning he went out with a reference book, a haversack and a canteen, and he didn't show up again until dark. Cap didn't mention that Straba had been officially surveyed ten years before or that results of this survey had been practically negative as far as adding to the Interplanetary Pharmacopoeia went. If Tri-Planet wanted to train its green personnel by sending them on a wild goose chase, that was all right with Cap.

But the old man had one thing that interested young Raine: his telescope mounted in a domed observatory on the top floor. Every night, Raine spent hours staring through that scope, sighting stars, marking them on the charts. Cap tried to tell him that those charts were as perfect as human intellect could make them. Raine had an answer for that too.

"Those charts are three years old," he said. "In three years a whole universe could be created or destroyed. Take a look at this star on Graph 5. I've been watching it, and the way it's acting convinces me there's another star, probably a Wanderer, approaching it from here." He indicated a spot on the chart.

He was efficient and persistent. He watched his star, checked and rechecked his calculation, and in the end, to Cap's amazement sighted the Wanderer almost exactly where he said it would be.

That discovery only excited him more and after that he spent an even greater amount of time in the observatory. Then late one night he came to the top of the stairs and called for Cap.

Cap went up to the scope, and at first he didn't see anything. Then he did see it: a darker shadow against the interrupted starlight.

"It's a ship," the old man said.

Raine nodded. "My guess too. But what's it doing out of regular space lanes?"

"You forget you landed here yourself. Straba does occasionally attract a visitor. Her crew may need water or food."

Raine shook his head. "I hedge-hopped in from asteroid, Torela. This fellow seems to be coming from deep space."

They continued to watch that approaching shadow, taking turns at looking through the scope. It seemed to take a long time coming; but finally there was a roar and a rush of air and a black shape hurtled out of the eastern sky. The two men ran outside where Cap began to curse volubly. The ship's anti-gravs were only partially on. It had hit hard, digging up three hundred yards of the sixteenth fairway and completely ruined two greens.

Then the dust cleared and the two men stared. The ship was a derelict, a piece of space flotsam. There was no question about that. It was also a Cyblla-style coach, one of the first Earth-made passenger freighters to utilize a power-pile drive, designed when streamlining was thought to mean following the shape of a cigar. On her bow was a name but meteorite shrapnel had partially obliterated the letters.

"Jingoes," said Raine, "I never saw a ship like this before. She must be old—really old!"

The hatches were badly fused and oxidized, and it was evident that without a blaster it would be impossible to get in. Cap shrugged.

"Let her stay there," he said. "I can make a dog-leg out of the fifteenth, and keep the course fairly playable. And if I get tired of seeing that big hulk out of my dining room window I can always plant some python vines around the nearside of her."

Raine shook his head quickly. "There's no telling what we may find inside. We've got to find an opening."

He went over the ship like a squirrel looking for a nut. Back under her stern quarter, just abaft her implosion plates, he found a small refuse scuttle which seemed movable. He took drills and went to work on it.

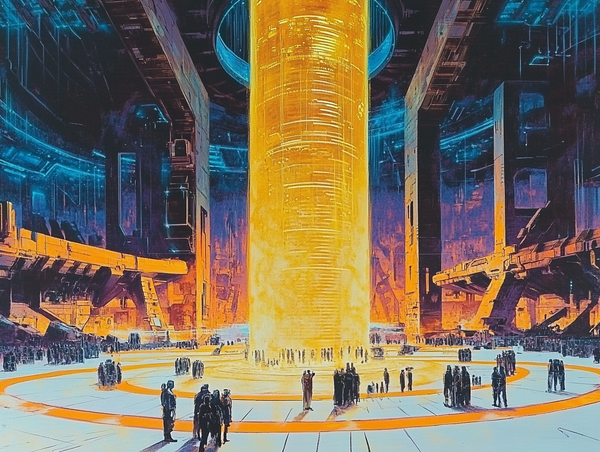

Three hours later the two men were inside. There was nothing unusual about the crew quarters or the adjoining storage space. But when they reached the control cabin they stood and gaped.

It was like entering a museum. The bulkheads were covered with queer glass dials, and several panels of manual operating switches. The power-pile conduits were shielded with lead—lead mind you—and the lighting was apparently done with some kind of fluorescent tubes bracketed to the ceiling. It brought Cap back to the time he was a kid and his grandfather told him stories and legends of the past.

Just above the pilot's old-fashioned cosmoscope was a fancy metal plate with the ship's name stamped on it. Perseus!

"Do you know what ship this is?" demanded Cap, excitedly.

"I can read," said Raine.

"But do you know its history ... the story behind it?"

Raine shook his head without interest.

Cap Barlow was still staring at the nameplate. "Perseus!" he repeated slowly. "It goes back to the First Triad Empire when the planets of Earth, Venus and Mars were grouped into an Oligarchy, when Venus was still a frontier. Life there was pretty much a gamble in those days, and the Oligarchs enforced strict laws of eugenics. They set up Marriage Boards and all young men and women had to undergo physical and mental examinations. Couples were paired off only after scientific scrutiny. In other words it was a cold-blooded system which had no regard for what we call love."

The old man paused. "Did you ever hear of Mason Stewart?" he asked suddenly.

Raine shook his head.

"As an individual he's pretty well forgotten today," Cap said. "I suppose you might call him a promoter. At any rate he figured a way to make himself a few thousand extra credits. He got hold of two condemned passenger freighters and with a flair for classical mythology named them Perseus and Andromeda."

Raine, listening, lit a cigarette and blew a shaft of smoke ceiling-ward.

"The Perseus was moored in North Venus," continued Cap. "The Andromeda, in the South. Stewart managed to spread the word that these two ships would be heading for Alpha Centauri to start a new colony. He also let it be known that the passenger lists would be composed of couples who were in love with each other without scientific screening or examination."

"Well, what happened?" demanded Raine with an air of acute boredom.

Cap bit off a piece of plug tobacco. "The rumor spread, and berths on the two ships sold for fabulous prices. Of course, the Constabulary investigated, but that's where Stewart was clever. The couples were to be split up: all females in one ship, all men in the other. The Constabulary warned them that it would take years to cross such an immense distance—those were the days before the Wellington overdrive, of course.

"But the couples wouldn't listen, and the two ships took off. People of three worlds made a big fuss over them. The theme invaded the teletheater and the popular tape novels of the day. Newscasters went wild in their extravagant reports.

"And then the truth came out. Stewart got drunk and let slip the fact that the boosters on the two ships were absolutely worthless and capable of operating for only a short time. By then the ships were several hundred thousand miles beyond the System and out of radio range. Rescue ships were sent out but found nothing though they went as far as they dared. Stewart was jailed and executed. That's the story of the Perseus."

Raine nodded and ground his cigarette stub against a bulkhead. "Let's get on with the examination," he said.

They continued down the dark corridors, Raine leading the way with a magno search lamp. Some of the cabins were in a perfect state of preservation. Others were mere cubicles of rust and oxidation. Once Cap touched a chair which apparently had been made of wood or some similar product; it dissolved into dust on the instant.

This was the Perseus, the ship which had carried the male passengers of that strange and ancient argosy, but as yet they had come upon no skeletons or human remains. What then had happened to them?

Five minutes later they entered the captain's cabin and found the answer. On the metal desk, preserved in litnite, lay the rough log. Cap picked it up, opened it carefully and began to read:

January 21—All hands and passengers in good health, but God help us, booster reading: zero-zero. By radio we have learned that our sister ship, the Andromeda, is also without auxiliary power and adrift. Such a dual catastrophe would certainly argue for something other than coincidence.

Our charts show an asteroid of sizeable proportions to lie approximately midway between the two ships. Under ordinary circumstances I would order the lifeboats run out at once and attempt to reach this planetoid, hoping that by some miracle it will be capable of supporting life. But the circumstances are far from ordinary.

We sighted them at 4:30 P.M., Earth-time, a few moments after the booster went dead and the ship lost steerageway. Absorbers! They hover out there in space, clearly visible through the ports, waiting for us to open the airlock. There are two of them, but even as I write, one has turned and with unfailing accuracy has headed in the direction of the Andromeda.

Absorbers! What a world of myth and legend surrounds them. Are they organic or inorganic? I do not know. I only know they have been mortally feared by sailors since the first rocket blasted through Earth's orbit. They are what their name implies: devourers of life, with the peculiar, apparently meaningless power of transforming themselves into a physical facsimile of their victims.

One of them is out there now, swirling lazily like a miasmic cloud of saffron dust....

Cap handed the book to Raine who read it and handed it back without comment. And at that moment Cap saw the kid in his true light: a cold-blooded extrovert who was interested in the ship only for what he could get out of her.

Next day, without asking permission, Raine began the task of dismantling the Perseus. He knew he had a potential fortune at his fingertips, for every portable object he could transport back to Earth or Venus would bring a high price from curio-hungry antique hunters.

For a week he worked almost unceasingly at the salvage operation. He unscrewed the ship's nameplate and made a little plush box for it. He took down the dials of the cosmoscope, the astrolog and other smaller instruments and made them ready for shipment. He stripped out the entire intercom mechanism, the old-fashioned lighting fixtures, to say nothing of the furniture and personal effects which hadn't spoiled by time.

It was on a Sunday evening that matters came to a head. In the early dusk Straba's twin moons were well above the horizon, shining with a pale light. Cap was in the kitchen brewing himself a cup of coffee when through the window he saw Raine emerge from the Perseus and carry an armful of equipment across to the little lean-to shed where he stored the salvage. He came out of the shed and something prompted him to look forward. An instant later he ran to the house and took the steps three at a time to the observatory.

He was up there a quarter of an hour before he came down again, a queer look on his face.

"Mr. Barlow," he said, "what's that thing that looks like a gun emplacement on the flat on the other side of the house?"

"That's exactly what it is," Cap told him. "A Dofield atomic defender. I've had that gun here a long time. When I first set up housekeeping on Straba, this part of the System was pretty wild. Pirates weren't unusual."

"What's its range?"

"Well, I don't know exactly. But it has a double trajectory that makes it a pretty potent weapon."

Raine looked at the old man for a long moment. "You probably don't believe in coincidences," he said. "But come upstairs. I want to show you something."

Cap followed him up to the observatory and looked through the scope. At first he couldn't believe his eyes. If he had been alone he would have said he was dreaming.

But there it was, a miniature satellite caught helplessly in the planet's polar attraction, midway between Straba's twin moons. He was looking at another antiquated space vessel; a ship that almost detail for detail was a replica of the Perseus. The truth dawned on him gradually.

It was the Andromeda—the sister ship of the Perseus!

The kid didn't hurry himself, bringing in the Andromeda. For two nights he did nothing but watch the sister ship through the scope. Then he carefully removed the preservative covering from the Dofield defender, cleaned and oiled the barrel and made the gun ready for a charge.

"If I can put a shot abaft her midsection," he said, "it might spin her out of polar draw long enough to fall into Straba's linear attraction...."

"Why don't you take your ship up and tow her in?" Cap said.

Raine shook his head. "Too dangerous. I'd have to come to a dead stop to fasten my grappler and at that range I'd likely become a satellite myself."

Meantime the Perseus lay neglected save for the tour of inspection Cap took through her on Friday morning. Cap hadn't been in the ship since Raine had started his salvage operations, and the old man was curious to see how work had progressed.

He entered through the refuse scuttle and proceeded to the control room. The bulkheads were bare expanses with only a few nests of torn wires and broken conduits to show where the dials and gauges had been ripped from their mounting places. The place looked desecrated and defiled.

Cap left the control room and mounted to the pilot's cuddy. Here, too, Raine's work was in evidence. The old man stood there, looking at the dismantled chart screens and thinking about the ship's strange and tragic past.

Her lifeboats were gone and the inner door of the airlock was still open. Her passengers and crew must have attempted escape in the end. Had they managed to slip by the Absorber and reached the asteroid, the name or chart number of which the captain had neglected to mention in the log? And were there such things as Absorbers or had the captain under stress of the situation given in to his emotions and flights of fancy.

Cap had heard the usual sailors' stories, of course. How a freighter had come upon one of them off Saturn's rim and sent out a gig to investigate. How the gig and all men in it had simply dissolved and become a part of the writhing cloud of mist. And how that cloud had then slowly coalesced into the shape of the six men and the gig.

As he stood there, Cap abruptly became aware of a vague pulsation, a rhythmic thudding from far off. He put his ear to the wall. The sound lost some of its vagueness but was still undeterminable as to source.

He went down the port ladder to the 'tween deck. Here the sound faded into nothingness, only to return as he descended the catwalk to the engine room. But in that cavern-like chamber he became conscious of something else.

He had a feeling he was surrounded by life as if he stood within the body of a living intelligence whose material form included the ship itself.

Clearly audible now was that distant thud ... thud ... thud ... like the beating of a great heart.

Saturday Raine announced he was ready to "shoot down" the Andromeda. Unfortunately Cap figured he wouldn't be there to see the show. He had had a signal from one of his weather-robots on the dark side of the planet that morning, reporting that a cold front was moving down and the migration of the Artoks was about to begin. The Artoks could be mighty troublesome when they came en masse. If Cap didn't want his golf course eaten to the roots he'd have to stop them before they started. The generators which powered the barrier wires across the Pass would have to be turned on and the relay stations set in order.

It was late before he made his return. Dusk had set in and the Straba's twin moons were riding high when he reached the hill over-looking the house. On the flat below him he could see the moonlight glint on the barrel of the Dofield defender, and he could see Clarence Raine standing by the gun as he made preparations to fire.

For a moment Cap stood there, drinking in the scene: his golf course spread out in the blue light like a big carpet and in the center of it the black cigar-shaped Perseus. There was something virile about that antiquated ship, something different from the Andromeda he had seen through scope. It was as if the Perseus were all masculine, while the Andromeda were its daintier feminine counterpart.

And then Raine touched the trigger. There was an ellipse of yellow flame, a mushroom of white smoke and a dull roar. Cap was flung backward by the shockwave. The hills fielded the explosion, flung it back, and the thunder went grumbling over the countryside.

In the empty silence that followed, Cap's wrist watch ticked off the passing minutes. The moonlight returned from behind a passing cloud, to reveal Raine by the Dofield defender, binoculars to his eyes. Time snailed by. The night was passing.

And then the roar came again, this time from above. Cap saw a great cylindrical shadow slanting down from the sky. The Andromeda struck far out on the flat beyond the house. It struck with a crash of grinding metal and crumbling girders.

For an instant after that a hush fell over everything. And then from the Perseus in the golf course came a sound, low at first, growing louder and louder. To Cap it sounded like a moan of anguish, of hatred and despair that seemed to issue from a hundred throats.

The Perseus trembled, began to move.

Cap stared. The ship moved on its belly across the fairway. Like a timeless juggernaut it entered the flat and slid out across the tableland toward the crumpled wreckage of its sister vessel.

Raine twisted about as he heard the thunder of that advancing hulk. Fear and disbelief contorted his face. He uttered a cry, leaped from the mount of the Dofield and began to run wildly across the flat. For an instant Cap thought he was going to reach the first low hillock that led to higher ground and safety. But Cap had reckoned without the terrific drive of that vessel.

Was it the Absorber—that strange creature of outer space—which had transposed its own inexplicable life into the shell of the dismantled Perseus and now was that ship alive with all the ship's hates, joys and sorrows? Organic into inorganic—a transmutation of a supernormal life into a materialistic structure of metal ... cosmic metempsychosis too tremendous for the finite mind to grasp.

The Perseus came on, bowling across the flat like a monster of metal gone mad, grinding over rock outcrop and gravel, throwing up a thick cloud of dust. It came on with a terrible fixation of purpose, with a relentless compulsion that knew no halting. It met and engulfed the helpless figure of Clarence Raine and a cry of mingled hate and triumph seemed to rise up from its metal body.

The Perseus continued along the moonlit plateau, heading straight for the wreckage of the Andromeda. Not until it had reached that formless mass did it stop. Then it shuddered to a standstill and ever so gently touched its prow to the prow of the sister ship.

For a long moment Cap stood there motionless. Then, head down, he slowly made his way down the hill toward his house.