The Ordeal of Lancelot Biggs

Lancelot Biggs navigating space conflicts and diplomacy with humor and ingenuity amid absurd bureaucracy.

Written by: Nelson S. Bond

Provided by: Project Gutenberg

Well, like it says in the old adage, "Things equal to the same thing gather no moss."

When the Corporation that under-pays us snatched the Saturn off the freight shuttle and turned it into a trouble-shooter for special assignments, we thought we were getting a break. Huh! We were. "Break" is just another word for "bust." The result of our alleged "promotion" was that for a fractional increase in salary we worked twice as hard at jobs ten times nastier than any we had ever tackled before.

Like for instance the night Cap Hanson and I—I'm Bert Donovan, bug-pounder of the Saturn—were at the home of Lt. and Mrs. Lancelot Biggs. Biggs is, of course, the First Mate of our void-mangling jalopy. A year ago he married the skipper's daughter, Diane.

We were sitting around, chatting about this and that and the other inconsequential truffle, trying to look calmer than we actually felt, when the telephone jangled. "Bet it's a wrong number!" I said—and picked it up.

I was right. It was a Wrong Number named Cheeverly, Assignment Clerk at Long Island Spaceport. He said, "Salujo, Sparks. Is Captain Hanson there?"

"Present," I said, "but not accountable for. Listen, Dracula, how about calling back tomorrow or next month?"

He snapped, "This is official business, Donovan! Put him on before I report you!"

So I handed the receiver to the Old Man, and for the next few minutes Diane and Lanse and I eavesdropped upon one of those unintelligible half conversations between Hanson and the drip at the other end of the wire.

"Yeah?" said the Old Man. "Yeah, this is Hanson.... Eh? Eh, what's that?... But Cheeverly, I.... What?... But I'm on furlough, man! The staff and crew of the Saturn were granted a three week vaca.... Oh! Oh, I see! Emergency, eh? Well, if we have to. But can't you find some other ship to.... Mmm-hmmm! I understand. Yes. Yes. Very well. I'll get in touch with my men immediately...."

He hung up and turned to us gravely. I think we all knew what he was going to say before he said it. Diane cried, "Oh, no, Daddy! No! Not now!" And Biggs asked, "What is it, sir? I hope they don't want us to—?"

Hanson fumed, "They do, dingbust 'em to Hades! It's an emergency mission. We're to lift gravs immediately!"

"Lift gravs!" exclaimed Biggs bleakly. His lump of a larynx leaped like a lemon in his scrawny neck. "But, Dad! I can't go now!"

His jaw sagged to his wishbone, making him homelier than usual. And, brother, that's saying something! Lancelot Biggs is a lot of things. He's a genius, for one, and he's slightly whacky, for another. Also he's one of the grandest friends a guy ever had. But even his doting mother could not honestly call him good looking.

He's about as tall as an old-fashioned hatrack, and built along the same general lines. He's got more bumps and knobs on his gangling frame than a hyperthyroid cucumber. Of these assorted protuberances, the most prominent is an Adam's-apple which bulges from his throat like a half-swallowed egg, and jiggles up and down when he's excited like a jitter-bug on an innerspring mattress.

He was excited now, and said voice-box was cavorting horribly from N to S and return in non-stop flight.

"I can't go now!" he repeated starkly. "Not now, of all times, Dad—"

Hanson shook his head regretfully.

"It ain't a case of can or can't, Lancelot. It's a case of got to. There's trouble on Themis again."

I said, "Themis—again! You mean another ship—?"

"That's right," nodded the skipper. "Attacked and smashed to smithereens. Not a man left alive. Yes."

"But that's impossible!" I cried. "Only last month the S.S.P. announced that a peace pact had been signed with the Thagwar of Themis. The natives of that satellite agreed to join the Solar Union—"

"Them Themisites," growled the Old Man, "keep their pledges about as good as them Japanese you read about in the hist'ry books. The little yellow squirts the United Nations had to wipe out a couple hundred years ago. This makes the sixth time the Thagwar has signed a peace pact. And it's the sixth time he's broke it. So—"

"So," I said, "we're elected, eh?"

"That's the ticket."

Lanse Biggs' jaw tightened. He said stiffly, "I'm afraid this is one time I shall not be able to obey orders, sir. I—I can't go with you!"

My heart did a flipflop. I understood, and heartily sympathized with Biggs. He wanted to be on Earth right now. Because—well, like a professional grape-farmer, he had raisins of his own.

But I knew what his outright refusal meant. The IPC is a hardboiled corporation. When it issues an order, it expects obedience—or else. If Lanse refused to make this expedition, he would not only lose his rating and his chance to go up for Master's papers—an examination he was planning to take in the very near future—he might also lose his job!

Furthermore—and if this sounds selfish, pardon my sullen accent!—I hated to think of making a truly dangerous trip without Lieutenant Biggs on the bridge. That brilliant wingding has pulled so many bunnies out of the derby, saving our individual and collective necks with such monotonous regularity, that we'd be utterly lost without his assistance.

But I said nothing. After all, this was a question Biggs must decide for himself.

As it turned out, though, it was not I, nor the Old Man, nor Lancelot, who solved the problem. It was Mrs. Biggs. In a calm, decisive voice she said, "But, Lanse, dear—such commotion! Of course you will go!"

"What!" blurted Lanse. "And leave you? Never!"

"Stuff," sniffed Diane, "and nonsense! Stop talking like a cheap play. What earthly good are you doing here? Not a bit! But out there, men have died ... betrayed by a race of scoundrels. Brave men. Spacemen like yourself. Your duty is plain. You must go. You have no choice."

"B-but—" protested Lanse.

"But," interrupted Diane, "nothing! Now, I'm tired. You boys run along and clean up this little job. I'll be here at home, waiting for you."

Biggs asked apprehensively, "And—and you'll be all right while we're gone? You're sure—"

"Certainly I'll be all right," declared Diane. "Now, lift gravs, sailors! And—good luck!"

So we went. It was one hell of a job collecting the Saturn's crew. Some of them were miles away, several of them were—well, let's be charitable and say, "unshipshape"—and all of them were madder than an alizarin dye at having their leaves cancelled.

But none of them were foolhardy enough to refuse the order. So, to make a long story less so, several hours later the Saturn roared from its mooring cradle, all jets blasting. And we were off to Themis.

Well, the planet Saturn is approximately nine hundred million miles from the Sun, and (since it was currently on our side of that central beacon) about 800,000,000 from Earth. In the good old days B.B.—Before Biggs—that would have meant a voyage of weeks. But since our ship was equipped with Lancelot's invention, the V-I (or "velocity-intensifier") unit, which enables spacecraft to attain speeds limited only by the critical velocity of light, we could expect to reach our destination in a trifle more than ten hours.

To forestall cracks from Earthlubber mathematicians who point out that 186,000 x 60 x 60 would give us a cruising speed of almost seven hundred million m.p.h., let me explain that you have to let the hypatomics warm for about five hours before you can cut in the V-I unit. Then the unit has to be switched off at least an hour before you reach your objective so you can decelerate without breaking every bone in your head.

Thus we had a ten hour trip ahead of us. So, as the Saturn jogged along outward into space, I sat back and tried to remember everything I'd ever heard about Themis.

It wasn't much. I knew that in 1905, Pickering, the discoverer of Phoebe, had first spotted Saturn's tenth satellite. He had named this tiny body Themis, after the goddess of Law and Order. Which, in view of later events, was a huge and mirthless horselaugh.

Then something queer happened. Themis—disappeared! Yeah, that's right. It got lost! Can you imagine "losing" a cosmic body about 300 miles in diameter? Well, that's exactly what the astronomers of the Bloody Twentieth Century did.

According to their record books, they hunted for it time and time again, but never relocated it. Finally they decided astronomer Pickering must have been sopping up too much spiritus frumenti the night he discovered the satellite, and they expunged its name from the records.

Which was, of course, a terrific boner ... because it was there all the time! It was rediscovered in 1983 by the staff observers of the Goddard Memorial Telescope located in Copernicus Crater on Luna. And in 2031 A.D. it was visited, charted, and claimed in the name of the Interplanetary Union by the Space Patrol rocket Orestes on a settlement investigation flight. Only nobody went to live there.

For one thing, it was too small pickings to bother with. During the Space Rush of 2030-80, everybody who could beg, borrow or steal a ride on a ship was hightailing it to the more important planets. Venus, Mars, Mercury, the asteroids. Later, the Jovian satellites became popular. Slowly the frontiers pushed farther and farther out from Sol. Until now adventurers were willing to take a squint at any body in space which boasted soil, air, and a modicum of gravity.

So at last, after long years of ignoring them, Earthmen were trying to become palsy-walsy with the Themisites. Oh, yes, Themis had natives. Humanoid aboriginals, not terribly unlike Earth's own children, except that they had four legs instead of two.

But our side wasn't getting anywhere, and in a rush! As the Old Man had said, six times a Patrol party had landed on Themis, and six times signed a peace pact with the ruler, or Thagwar, of that globe. But each time the pact had been ignored by the Themisites as soon as a party of colonists attempted to land. The defenseless cruise-ships had been set upon, destroyed, their cargoes stolen, and their passengers brutally slaughtered!

So now here we were, blithely barging in where sensible angels might justifiably hesitate to tread. It didn't make sense. I asked the skipper about it.

"Look, Cap," I demanded, "maybe I'm sort of slow on the intake, but how come we draw this assignment? Since the Themisites seem to want trouble, how come the Space Patrol doesn't go busting out there with rotors primed and a couple battalions to occupy the world?"

"On account," explained Hanson impatiently, "Themis is populated by a race with an intelligence quotient of more than .7 on the Solar Constant scale, Sparks. And also because the race has a recognized form of government.

"Accordin' to interplanetary law, colonization of civilized bodies can only be carried out with the permission of the native inhabitants, and aggressive occupation is forbidden when those inhabitants possess humanoid intelligence."

"Meaning," I asked, "what? We aren't allowed to grab Themis unless the Themisites let us?"

"Meanin'," snorted the Old Man, "that if you was the only inhabitant of Themis, the S.S.P. wouldn't have nothin' to worry about. But the hell with that. I didn't come here to bandage words with you. I come up to ask you if you happened to notice the funny way Lanse is actin'."

I had. I nodded sombrely.

"Moping around," I acknowledged, "like a biddie on a china egg. But you can't expect anything different, Skipper. After all, he didn't want to leave Diane at a time like this."

"Of course not. Neither did I. But since we had to, we might as well buckle down and get the job tooken care of as quick as possible. Anyway, you're keepin' in touch with home, ain't you?"

"Absolutely. Holding an open circuit every minute. But don't worry about Biggs, Skipper. He'll be all right as soon as we actually get to work."

That's as far as I got with my Pollyanna glad-talk. For at that moment the intercommunicating system rasped into life, and in the reflector appeared the baffled pan of Dick Todd, our Second Mate. Dick was so nervous he had to lick his lips three times before he could grease out a word. At last:

"S-s-skipper!" he managed.

"Yeah? What is it?"

"Th-th-themis! We're pulling into Themis—"

The Old Man glanced at his chronometer and nodded.

"O.Q. So we're dropping gravs on schedule? So?"

"N-n-nothing," gulped Todd, "except that Themis has d-d-disappeared! The automatic alarm system is going crazy. According to it, there's a large cosmic body right in front of us—but we can't see a thing!"

I said, "Oh-oh!" and groped for my transmitter key. But before I could start pounding the bug, Hanson grabbed my wrist.

"And just what do you think you're doing, Sparks?"

"I don't think," I told him, "I know! When people see things that aren't there, I know what to do. Hide the bottle. But when they start not seeing things that are there, that's all, folks! I'm calling the S.S.P. base on Luna and asking them to rush a hospital ship out this way, immediately if not sooner. A nice, pretty hospital ship equipped with soft, hemstitched straitjackets—"

"Don't be a dope," roared the Old Man. "Todd don't talk nonsense for no good reason. There's something screwy goin' on around here. I want to know what it is. Come on!"

And he galloped from my turret like a bolt of goosed lightning, hauling me along in his wake by sheer suction. We hightailed it through the corridors, up the ramp, and onto the bridge. There we found both Todd and Biggs. Todd was still a delicate shade of bilious green, but he was hunched over the plot table, scribbling hurried calculations. Biggs was in the pilot's bucket seat, punching away at the studs as cheerfully as if this were a routine test flight in home atmo.

He glanced around as we came in, and his eyes popped out on stalks. He half rose from his seat.

"A—a message, Sparks?" he quavered.

I shook my head.

"No word yet," I reassured him. "I'll let you know. Meanwhile, what's the trouble around here?"

"Trouble?" repeated Lancelot wonderingly.

The Old Man groaned and pawed at what little remains of his hair.

"Don't look now," he rasped, "but didn't Todd call me a couple of minutes ago with some wild-and-woolly tale about Themis disappearing?"

"Oh—that!" smiled Biggs gently. "I thought for a second you meant there was something wrong. Why, yes, Dad. Themis has disappeared—temporarily. Oddest thing—"

"Talk sense!" I moaned. "Todd said something about there being a large body in our path, too. Did it—" I took a look at the central vision plate which reflected nothing between us and the far stars—"did it go away?"

"Oh, no," drawled Biggs nonchalantly. "It's still there."

"Still there!" I looked again, more closely, at the vision plate. It was as bare as a debutante's backbone at a ball. "What's still where, Lanse? Have you gone off your gravs, or are my optics myopic?"

"The large body," said Biggs blandly. "It's Themis' moon. It's there. Three points to starboard, and one degree to loft."

"Themis' moon!" croaked the Old Man. "What in Hades are you talkin' about, Lancelot! Themis is a moon!"

"I know," agreed Biggs. His larynx bobbled pleasantly. "That's the curious part of it. This is the first time in the solar system that any satellite has ever been found to have a satellite of its own! But we've located it, charted its trajectory, and cross-checked our calculations—haven't we, Dick?"

Todd looked up from the plot table.

"That's right," he said hollowly. "Themis has got a moon of its own. An—an invisible moon!"

"Invisible moon!" The skipper and I did a twin act.

"Yes," said Biggs. "You know, I believe that's why Themis—er—'disappears' periodically. It is circled by a large, opaque satellite with the peculiar property of being able to bend light waves around itself. Consequently, every time the moon, revolving around its primary, comes between Themis and observers, Themis is occulted—and disappears!"

The Old Man looked at him like he had just grown a second head.

"B-but that's impossible, son!" he gasped.

"Oh, no," said Lanse quietly. "Unlikely, yes. But not impossible. Because—well, because the situation does exist, you see." He clucked thoughtfully. "Strange, isn't it, that we should be the first to find it out? After these many years. But that's the Laws of Chance for you. Every other time a ship visited Themis, the invisible moon must have been on the far side."

Hanson was fidgeting like he had wasps in his weskit. Now he broke in, "That's all very interestin'! But how about the chances of our crackin' up on this aforesaid moon-of-a-moon?"

"Oh," replied Biggs negligently, "that's all taken care of. We've plotted a new trajectory around it. We should see Themis again in a moment—Aaah!" He breathed a sigh of satisfaction. "There she is! Nice looking little satellite, isn't it!"

And true enough, Themis was beginning to appear in the vision plate before us. A weird looking sight it was. A thin sliver of terrain at first ... then widening, growing into a full sized cosmic body as it stopped being occulted by its phenomenal little companion.

Biggs punched the intercommunicating stud and spoke to the engine room.

"All right, Mac," he called. "You can cut the V-I. Prepare to land in about fifty minutes." Then he turned to us again. "Remarkable thing, what? Some day when we're not so busy we'll have to drop jets on that invisible moon, eh? Should be an interesting visit to make."

The skipper groaned feebly.

"Interestin'! He finds an invisible moon, figures a trajectory around it, then says it's—Oooh! Let me out of here! I'm feelin' heat-waves!"

I grinned at him consolingly.

"Cheer up," I told him. "I know just how you feel. Only it's not the heat ... it's the humility."

So that was that. The next hour was taken up with routine stuff. Decelerating to atmo velocity, cruising over Themis until we located the capital city of Kraalbur, where the Thagwar maintained his royal residence, dropping to a stern-jet landing ... that was all child's play for a spaceman like Lt. Lancelot Biggs.

Thus it was that a short while later, armed to the teeth and ready for any eventuality, our foray party of ten men stood in the lock of the Saturn, listening to Hanson's final instructions.

"Be quiet," he advised us, "be calm ... but above all, be careful. These Themisites is as untrustworthy as three-of-a-kind in a gamblin' joint. Our orders is to improve relations, not make 'em worse ... so act accordin'ly. We'll treat them exactly like they meet us. If they greet us friendly, we'll be nice. But if they get tough—"

"Well?" asked one of the crew.

"Give 'em the works!" said the Old Man succinctly, and nodded to his son-in-law. "O.Q., Lanse. Open up!"

The airlock wheezed asthmatically, and we stepped out upon the soil of the satellite Themis.

A huge mob of natives had gathered around to greet us. They were a weird looking outfit. Sort of like men on horses, you might say, or like those old Centaurs you read about in mythology books. Maybe that's where the legend of Centaurs originated; I don't know. The more man travels the spaceways, the more he discovers races of beings similar to the freaks and curiosities recorded in ancient myths. Lanse Biggs believes that once upon a time, thousands of years ago, before Earth's old moon crashed, destroying the civilization then existent, Man knew the secret of spacetravel, and legend is a record of things once seen and known. But I wouldn't know about that. I'm just a radioman....

Anyhow, these Themisites were sort of like us down to the tummy. But from there on they branched out into the equine family, being endowed with strong, muscular, quadrupedal bodies and postscripted with long, bushy tails.

But they were intelligent. No doubt about that. And surprisingly enough, they seemed friendly! One, their ruler, trotted forward and raised an arm in the cosmoswide gesture of greeting. He addressed us in Universale, the common language of space.

"Salujo, amiji!" he said. "Welcome to Themis, land of peace and brotherly love!"

Hanson gasped, "Get a load of that! Three days ago the four-legged punks murdered a whole crew of Earthmen, and now they yap about brotherly—"

"Maybe he's right?" I suggested thoughtfully. "You ever have a brother, Skipper?"

"Shhh!" whispered Biggs. He stepped forward, acting as spokesman for our team. "Greetings, O Thagwar of Themis! We come as emissaries from the Blue World, seeking to forge a bond of friendship between your people and ours."

"Friendship and peace," said the Thagwar grandiloquently, "are ever the desire of my race."

Lanse said, "We hear and believe, noble Thagwar. But evil tidings have lately reached our ears. It is told that a few days ago you led your people in mortal combat against a party from our planet—"

The Thagwar drew himself stiffly erect and shook his head in firm denial.

"That," he said in a tone of outraged dignity, "is not so! It was the old Thagwar who led that brutal assault."

"Old Thagwar? Then you have overthrown his government since—?"

"The former Thagwar," informed the Themisite leader, "has been removed from power. I am now Thagwar of Themis. I wish only friendship and peace between our peoples. And now," his eyes rolled hopefully, "have you brought the usual—er—tributes?"

"Tributes," of course, meant graft. Humanoid forms change with the planets, but human nature doesn't. However, we had come prepared, knowing the mentalities of our opponents. Lanse beckoned to a pair of our crewmen who lugged forward a crate packed with an assortment of the doolallies and thingamajiggers loved by abos like the Themisites. Mirrors, gaudy bits of costume jewelry, brightly-colored trinkets, yards of richly hued cloth, horn-rimmed spectacles, cheap cameras ... all that sort of thing.

Crooked? Sure. Taking advantage of ignorant savages? Posilutely. But, hell, you can't interest uncultured aborigines in vanRensselaer atomo-converters and pre-Rooseveltian Era art treasures. Of course they'd be glad to get their paws on a few Haemholtz ray-pistols or a case of three-star tekel, but the authorities frown on the practice of supplying lower races with firearms, fireworks or firewater.

So Lanse handed out the gadgets to the Thagwar, who beamed with delight. And after that the negotiations were a snapperoo. We told what we wanted: permission for Earth's colonists to settle on Themis, the right to construct spaceports, and so on and so forth ... and the ruler said, "Yes ... yes ... yes," till he sounded like a phonograph needle caught in a worn groove.

There remained but one thing to be done. The formal signing of the treaty. So Lanse drew from his pocket the previously prepared sheets, and was just getting ready to help the Thagwar scrawl a legal "X" on the dotted line when a stir passed through the assemblage.

It was a nervousness, a jitteriness, you could feel! Heads craned upward to look at the sky, hooves pawed restlessly at the turf. And one by one, the centaurlike denizens of Themis began drifting away, cantering back toward the cluster of hovels which was their capital city.

Even the Thagwar seemed hesitant, uncertain. For a few minutes he tried to carry on like a bold, brave monarch. Then with a little whimper that sounded almost like a whinny, he picked up his bundle of loot and galloped away, too.

Cap Hanson's jaw dropped like a wildcat stock in a bear market.

"Well, I'll be!" he choked. "Now what?"

But Biggs had been studying the sky. Now he frowned.

"Night," he said.

"Eh?"

"Night," repeated Lanse, "or what passes for night on this peculiar little satellite. You see, Themis doesn't revolve on its axis, therefore it has no night or daytime as we on Earth know those periods. And, of course, since it travels about its primary so swiftly, and since Saturn itself emits so strong a gegenschein, occultation by the mother planet doesn't create perfect darkness.

"But Themis' invisible little companion swings about Themis. And whenever it comes between this world and the Sun a dark period ensues. I should judge we are about to experience one right now. Yes—see? It is beginning to get dark."

"You mean," stormed Hanson, "everything's called off on account of darkness? The pact ain't goin' to be signed?"

"Apparently not," admitted Lanse ruefully. "Almost all aboriginal races have a deep dread of darkness, you know. Well—"

He shrugged—"there's no sense in our waiting out here until the 'night' period ends. We might as well go back to the ship and be comfortable."

So we did.

Fortunately, the phony "night" didn't last long. Fortunately for me, I mean. Because as soon as we got to the ship, Lanse pranced along with me up to the radio turret, and there pestered the living bejabbers out of me to try to get some word from Earth. But that was strictly no go. My audio was humming like a tenor in a tepid shower. Static galore.

But at last the invisible barrier cutting us off from Sol's light slipped away, and once again we marched out onto the soil of Themis.

Marched out? Huh! This time we sauntered out. We were feeling very carefree and confident, you see, that everything was hunky-dory. Why not? We had been on the verge of signing the new peace pact when darkness interrupted us....

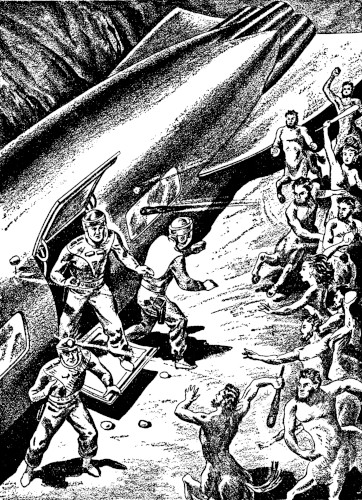

That blind, trusting confidence almost cost us our lives! The Themisites were again gathered around our ship. But when we stepped from the airlock—we stepped out into a hail of lethal fury!

We stepped out of the ship—right into a hail of rocks!

It was a good break for us that the Themisites had no modern weapons. A couple of Haemholtz pistols in the paws of capable users, or even one .54 millimetre rotor, and yours truly wouldn't be here to chronicle the ensuing events.

But the four-legged scoundrels' armaments were fortunately on the barbaric side. Stones and cudgels, crudely forged spears, incompetently carven bows and arrows that were as inaccurate as a real estate agent's descriptions ... these were the weapons with which we were assailed.

Cap Hanson caught a nice sized chunk of rock amidships, and one of the crewmen had his shoulder opened up by a wobbling spear, but those were our only casualties. Above the hub-bub and furore—the Themisites were howling like a mob of unleashed demons—Lanse cried, "Back into the ship, quickly!"

Which was a command requiring no repeat performance. For the next three seconds the airlock port looked like Bargain Day at the Girdle Counter. Then we were all inside once more, safe at home but sore as a student equestrian's coccyx.

The Old Man bellowed, "Unlatch the rotors! Treacherous villains, I'll learn 'em to attack Earthmen! We'll blast them clean off the face of their nasty, sneakin' little globe, the good-for-nothin' horses—"

But Lanse said, "No, Dad—please! Wait a while!"

"Wait? What for?"

"There's something distinctly unusual about this," pondered Lancelot gravely. "A few hours ago they were friendly; now they are screaming for our blood. I don't understand it. But you know my motto: 'Get the theory first!' If I can learn why they changed so abruptly—"

"What difference does it make why they changed? They did, didn't they? That's all that counts—"

"No, Dad. The important thing is not to overwhelm the Themisites, beat them into submission. It is to settle our differences for all time, establish an enduring peace—" He turned to me—"Sparks, get on the wire, will you? I want a complete report from Earth on the previous peace treaties signed with Themis. Who signed them ... when ... under what circumstances ... everything we can learn."

"O.Q.," I said. "It's your business. But my money bets on the Skipper's plan. 'Civilize 'em with a gun' is my motto."

Biggs shook his ungainly head disapprovingly.

"That form of reasoning," he declared, "died with the dictatorships. Now, get on the key, Sparks. And, oh—while you're at it, see if there's any news from Diane, will you?"

He was a very anxious looking gent. And no wonder.

Well, after that tempus fidgeted, as it has a habit of doing, the static had cleared, and I established contact with Joe Marlowe at Lunar III. He said he'd try to scare up the info I wanted, but it might take time. I told him to go ahead; I had more time on my hands than a professional watch repairer. So we dillied and dallied, and after a while back he came, loaded with more facts than Mr. Britannica put in his encyclopedia.

The Themis situation, it seemed, was plenty complex. The first peace pact had been signed eight months ago between the Thagwar of Themis and the Solar Space Cruiser, Ajax, Col. A. R. Prentiss commanding. Swell! Only two weeks later the Themisites had murdered in cold blood an agent sent there by the Cosmic Corporation to set up a trading post!

The S.S.P. had sent a second expedition. This party reported hostile reception. Then, after a whole day wasted in attempting to get in touch with the Thagwar, the Themisites had suddenly turned friendly—and signed a second treaty.

This one had lasted exactly four days. It was busted when the quadrupeds dittoed the craniums of a party of miners who dropped gravs for fresh water supplies!

Why go on? Expeditions Three, Four, Five and Six had all followed the same pattern ... an agreeable understanding followed by a swift kick in the nose. Our experience was no novelty; we were just number Seven on the Themisite hit-and-run parade.

"In view of the circumstances," Joe Marlowe wound up his report, "the authorities here suggest that Captain Hanson get the situation in hand and get the situation in hand and get the situation in hand and get the situation—"

I cut in on him—but quick!

"Hold everything!" I shot back. "Let's play like he now has the situation in hand. What happens next?"

"Let him contact the Thagwar of Themis," bugged Marlowe, "and contact the Thagwar of Themis and contact the Thagwar of Themis and contact—"

Biggs was in the turret with me. He can read code almost as well as I can. He stared at me curiously.

"What's the matter, Sparks?"

"Don't ask me," I retorted. "I only work here. It sounds like Marlowe's developed a bad case of digital hiccups! Oh, well, we've got the information we wanted, anyhow. I'll sign off." So I did.

Biggs asked, "And—and Diane?"

"No word yet. Joe will let us know. The circuit's still open. Well, you've heard the report. What do you make of it?"

Biggs said slowly, "I don't know, Sparks. It's very peculiar. I'll have to think it over—Yes? What is it?"

He spoke this last to the wall audio which had come to life. Cap Hanson answered from the bridge.

"Lanse, are you there, son? Listen, come up to the bridge right away, will you?"

Swift apprehension tightened Biggs' features.

"What's the matter? The Themisites getting violent? They're not attacking the ship?"

Hanson groaned like the guest artist at a seance.

"Just the opposite! Another of them phony 'nights' has passed outside since you two've been fiddlin' around up there. Now it's daylight again ... and there's a mob of Themisites gathered around outside ... wavin' banners and peltin' the Saturn with flowers! The Thagwar has just sent a messenger biddin' us friendly welcome to Themis!"

"Great growling guttersnipes!" I spluttered, "What's this all about? One minute they want to kill and boo ... the next they want to bill and coo! Why don't they make up their minds?"

"Probably," decided the skipper, "because they ain't got none. Lanse—?"

"We can't learn anything," said Biggs quietly, "in here. Let's go outside."

So for the third time in as many Themisian 'days', out we pranced, to be greeted by such hooraw and ballyhoo as you never saw. Those same centaurs who, a few short Earthly hours ago had been aiming lethal presents at our kissers were now aiming kisses at our presence! Their leader pranced forward gracefully and made a low bow before Cap Hanson.

"Greetings, Oh child of the Blue World!" he intoned. "As Thagwar of Themis I bid you welcome to our peace-loving little planet—"

"Th-thanks!" said the Old Man, and looked bewildered. "Lanse, son, suppose you—?"

But Lanse was staring curiously at the speaker. He nudged me and whispered, "Sparks, study the Thagwar! Do you notice anything ... well ... strange about him?"

"Sure!" I assented. "He looks like a veterinarian's mistake; is that what you mean? If it's the color of his eyes you're worrying about, you'd better ask somebody else. These Themisites all look the same to me. Like peas from the same pot."

"That's not what I meant," whispered Biggs. "What strikes me as being odd is that ... remember how proud he was of those ornaments we gave him before the 'night' period set in? He had himself all decked out like a Christmas tree. But now look at him! Not a single decoration!"

"Maybe," I suggested, "he's allergic to tin?"

"And on the other hand," mused Biggs, "that Themisite over there is wearing a bracelet and a brass curtain rod in his nose—"

He was perfectly right. The big boss of Themis was as barren of trinkets as a Pilgrim father. But standing in the background was one of his henchmen glittering like gilt on a joy-joint bar! It was whacky. The Thagwar didn't look to me like the kind of guy—or hoss—who would donate his "tribute" to a subject.

"There's something fishy about this," I said. "Ask him how come, Lanse ... just for the halibut."

"I will," said Biggs, and stepped forward to do so. But before he could pop the question, the Thagwar spoke up.

"Peace," he said hoarsely—no pun intended, pals! Lay down them bricks!—"Peace between your people and mine. And now—did you bring the usual tribute?"

"Usual tribute!" repeated the Old Man starkly. "Of course we did! We give it to you yesterday, you rascally old scoundrel. What's the big idea of—?"

The Thagwar's eyes darkened, and he pawed the ground fretfully.

"That is a mistake, Earthman! You gave me nothing!"

"Wha-a-at! A whole darn caseful of—"

"You gave me," repeated the Thagwar with increasing ominousness, "nothing! You offered a few baubles to the old Thagwar, possibly—"

Cap Hanson groaned and turned agonized eyes to his son-in-law. "Ain't that something, now! Another revolution! Now we got to pay off twice!"

Lanse nodded soberly.

"I suspected something like that. Yes, I'm afraid we must, Dad. Tomkins ... Splicer...."

He called to two of the crew. So we had to do it again. Go through the same old rigmarole. I'll spare you the details this time, since they were the same as before. We donated, the Thagwar accepted, then we started talking peace-terms. The pact was presented, the Thagwar studied it and this time—fortunately—succeeded in stamping it with his official O.Q. before Themis' invisible moon brought night again.

So at last our job was accomplished. As we entered the ship, Cap Hanson was jubilant.

"Thank goodness that's done!" he sighed happily. "And now—back to Earth! And Diane—"

Biggs' Adam's-apple bobbled convulsively in his lean throat. "I—er—I think we'd better wait just a little while longer, Dad," he said mildly.

"Wait? What for? We got the peace pact signed."

"I know. But don't forget, that's only the eighth in a long series of such 'peace pacts.' We'd better stick around a little while and see if they live up to it."

"Stick around a while! How long?"

Lanse glanced through the quartzite viewpanes and said, "Not long. Because—see? It's night again."

"Night! What's night got to do with it?"

"That," said Lanse seriously, "is just what I want to know. If I could only get the theory straight in my mind I might have the answer. Sparks—" He turned to me—"turn on the telaudio. Let's see if we can't get some word—"

So I did, but there was nothing cooking. The circuit was as cold as a divorcee's kiss. And that was bad, because Biggs was growing nervouser and nervouser by the minute. He wanted to get back to Earth so bad he could taste it. But that's Biggs for you. Thorough and painstaking if he undertakes a thing. And he wasn't going to leave Themis until he knew this situation was completely cleared up.

But at last the darkness outside began to lift, and Cap Hanson fidgeted.

"Well, here's what you were waitin' for, boy. Now what?"

"Now," said Biggs, "we see what happens. Are they coming back from their city?"

They were. The Themisites were galloping across the plains toward the Saturn again. They were the romping, roamingest bunch of mavericks I ever saw. "Yup!" I said.

"And—and their attitude?"

"Friendly, of course!" snorted the skipper. "Why shouldn't they be? Didn't we just sign a peace treaty with them? Lanse, I don't know what's ailin' you! You—"

He never finished his denunciation of Biggs. For at that moment the oncoming Themisites hove within hurling distance—and started hurling! Only this time it was not, as it had been a short while before, flowers. This time their expressions of "everlasting peace and affection" were offered with—stones, arrows, and spears!

Well, Hanson's roar of rage threatened to lift the top clean off the control turret.

"Dastards!" he screamed. "Vandals, murderers and things that rhyme with what I first called 'em! This is all I'm goin' to take from them four-legged scoundrels. Call up the men, Sparks! Tell 'em to man the guns! We're goin' to blast them murderin' skunks from here to Kingdom Come—"

"Wait, Dad!" pleaded Biggs feverishly. "I think I'm beginning to understand—faintly. If you'll give me just a little more time—"

"Time your Aunt Nellie! I've done all the delayin' I'm goin' to—"

It was at that moment the telaudio, which I had set to vocode any message which came in on the Luna circuit, began squawking. It was faint at first, and sort of garbled, with lots of static, but it cleared as it went along.

"Lieutenant Lancelot Biggs," it called, "aboard the Saturn—congratulations! You are the father of a fine baby boy!"

"B-b-b-boy!" gasped Biggs. His face turned every color in the spectrum, and a couple that haven't been invented yet. "A—a boy!"

"Yippee!" howled the Old Man, his thoughts of vengeance on the Themisites temporarily forgotten. "A grandson! I'm a grampaw! Yippee!"

"Congratulations, Lanse!" I said. "A boy, eh? Swell! Another Biggs in space, one of these days—"

"S-s-see if you can get Earth, Sparks," chattered Biggs. "F-f-find out how Diane is."

"Right!" I snapped. "I'll get at it immediately."

I started for the radio room. But before I had taken two steps the audio began talking again.

"Lieutenant Lancelot Biggs," it called, "aboard the Saturn—congratulations! You are the father of a fine baby boy!"

My face sort of blanched. I turned to Biggs. "Congratulations," I offered, "again, Lanse! Golly—two boys!"

Hanson demanded, "Whaddya mean, two boys! That's a repeat message, you dope!"

Lanse smiled sort of feebly.

"I—I'm afraid not, Dad," he said. "If it were a repeat message, Marlowe would have said, 'Repeat.' Sparks is right. I—I'm the father of twins!"

"Well, I'll be darned!" ejaculated the Old Man. Then, rallying, "Twins, eh? Good! That makes me two grampaws, eh? Fine! I'm twice as gla—"

He stopped, his jaw dropping strickenly. For again Joe Marlowe's voice was rolling through the control turret.

"Lieutenant Lancelot Biggs," it called, "aboard the Saturn—congratulations! You are the father of a fine baby boy—"

"G-g-gracious!" gasped Biggs, and fell into a chair. "Triplets!"

This time I addressed myself to Hanson. "Congratulations, Skipper," I said. "Now you're three grampaws. If Diane keeps this up, you'll be able to man a whole cruiser."

The Old Man's face was fiery.

"Now, hold everything!" he stormed. "This is goin' too far! Diane don't have to overdo it, just because we're not there! There's such a thing as—Triplets! I won't allow it!"

"What's the matter," I grinned at him, "afraid of the Three Little Biggs, Skipper. Don't be a big bad wolf!"

But even I didn't think it was funny when, at that moment, Joe Marlowe's familiar tones rolled through the room again.

"Lieutenant Lancelot Biggs," he called, "aboard the Saturn—congratulations! You are the father of a fine baby boy—"

"Gosh!" I gulped. "This is turning into a parade!"

Cap Hanson's face was a study in technicolor. His jowls were dangling to his third weskit button. But oddly enough, at this third dire pronouncement, Lancelot Biggs did not even wince. Instead, his eyes brightened; he rose from the chair into which, a moment before, he had tumbled.

"No!" he yelled. "Not a parade—a solution!"

"Huh?" I gaped at him. "Solution to what? The unemployment problem?"

"No, Sparks! All our troubles! Quadruplets? No! Triplets? No! Twins? No, not even that! Just one baby!"

"Y-you mean," I asked him, "that's a repeat message? But, Lanse, you know as well as I do Joe would have announced it as a repeat—"

"Certainly. But what we're hearing is the same message over and over again!"

"Huh!" Hanson forced the query, new hope in every wrinkle of his brow.

"Yes. Remember how Marlowe's orders got grooved before, Sparks? Well, this is some more of the same thing! I know why, too. And I also know why we've been having so much trouble with the Themisites!"

"Y-you do? Why?"

"The moon! The invisible moon—that's the answer! Tell me, Sparks—what sort of things are invisible?"

"Why?" I stammered, "dark things seen against a dark background ... light things seen against a light background ... objects marked with protective coloration...."

"And transparent things!" chortled Biggs. "Transparent things with just sufficient mass to cause refraction of light! That's what Themis' moon is made of! Pure, unadulterated galena in its natural form is a colorless, transparent substance, sufficiently opaque to occult Themis, but also with enough mass to refract normal light rays! And galena is—"

"I get it!" I hollered. "A natural wave-trap for radio transmission. Back in the early days of the Twentieth Century, galena was the substance used in the manufacture of experimental so-called 'crystal sets'!"

"By golly, you're right, Lanse! That satellite is large enough to capture and retain a record of Joe Marlowe's voice, and as it revolves it keeps re-transmitting it to us over and over again—"

"Lieutenant Lancelot Biggs," repeated the voice of Marlowe—"aboard the Saturn—congratulations! You are the father of a fine baby boy!"

"—like that!" said Biggs. "Yes! Notice how Joe's voice always catches a little just before he says 'congratulations'? It's been the same fault every time."

"O.Q.," broke in the Old Man. "Maybe you're right. You usually are. But what's that got to do with the way the Themisites keeps changin' their attitude towards us? Don't tell me they got galena in their veins?"

Biggs shook his head firmly.

"No, that's another question entirely. But it can be solved by the same theory."

"Huh?"

"Twins!" said Biggs. "Or, rather, multiple rulers! Sparks, you said you couldn't tell the difference between one Themisite and another—"

"That's right."

"Neither can I. Neither can any Earthman. That's why we've been unable to understand their psychology and—more important still—their form of government."

"Government!" burst in the Old Man. "Now he talks about government. What's that got to do with—"

"Why," explained Lancelot, "everything! The Themisites have one of the rarest forms of self-rule known. But one which early in the Greek civilization had its counterpart on earth. You see, they are an omnigarchy!"

"A who-ni-whichy?" I choked.

"Omnigarchy! From the Latin base omni-, meaning all! You see, on this world—everyone takes his turn at being Thagwar! Every day a new Themisite becomes master over his brethren until the next 'night' period. That is why the Thagwar we signed our pact with today denied having received any gifts. He told the truth. We had given our tributes to the Thagwar of the preceding day.

"That is—must be!—also why peace pacts have been broken with such regularity. Each succeeding Thagwar feels he, being now ruler, is entitled to a share of the 'spoils' that go with the signing of a treaty—and being not obligated to uphold the signature of a deposed Thagwar leads a movement against colonists in an effort to win his rights. The individual natures of these Thagwars dictates the form of movement. If the Thagwar is a naturally peace-loving creature he comes with soft words and flowers; if he is a brutal type, he attempts to take his tribute by force."

I demanded wildly, "But—but how the dickens are we ever going to form a permanent treaty with a race that changes rulers once a day? Especially when a Themisian day is only a couple of Earth hours?"

Biggs shrugged. "That," he declaimed, "is not our problem, but that of the Interplanetary Union. My private opinion is that, since Themis has a limited population, the best way to assure peace would be to buy over every single Themisite. Of course, that means a terrific initial expenditure, but—"

"But," said the Old Man, "we've done what we was sent here for. We signed a peace pact—which ain't worth the paper it's printed on—and we found out why all former treaties was failures. So if you ask me, the best thing we can do is git out of here before one of them periodic Thagwars, smarter than the rest, discovers a way to wreck our ship. What say, son?"

"That," nodded Biggs, "would be my idea, too. Our task is finished; we'll leave it to the Space Patrolmen to figure out the rest. Come on, Dad—let's lift gravs for home and Lancelot, Junior!"

"For Lance—!" The Old Man frowned. "Oh, no! No more silly names like that in our family. That young man's name is gonna be Waldemar—after me!"

"Lancelot!" said Lancelot stubbornly.

"Waldemar!" said Waldemar Hanson the same way.

"Lancelot!"

"Waldemar!"

So we all went home and met Christopher Biggs. Only trouble with those two shipmates of mine is that they forgot Diane Hanson, who, being the daughter of Waldemar and the wife of Lancelot, has a stubborn streak of her own.

Kit Biggs weighed seven pounds and eight ounces. He and his mother are both doing fine, thanks. Biggs is doing O.Q., too. He's got a new title now. Around his home, that is. He's First Mate in Charge of the Three-Cornered Pants Department.

But—what do you expect? After all, life is just one damp thing after another....

THE END